The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which disappeared off the map as a result of the Partitions at the end of the eighteenth century, had included the homelands of many nations. During the nineteenth century many Poles dreamed of rebuilding the Polish Republic with the same historical borders. However at the beginning of the twentieth century, a period of awakening national consciousness among the nations of central and eastern Europe, this issue required an innovative solution, particularly because the concept of creating nation states based on ethnic criteria was becoming increasingly popular.

The two biggest Polish political camps — one grouped around the National Democracy movement and its leader Roman Dmowski, the other around the Polish Socialist Party which for a period was led by Józef Piłsudski — laid plans about the territorial shape a free Poland might take in the future. Dmowski’s nationalist camp wanted to implement the concept of “incorporation”. At the core of this concept was the proposal to include within the boundaries of the Polish state only those territories in which either the majority of the local population were Poles or which could quite easily be assimilated and become Polish.

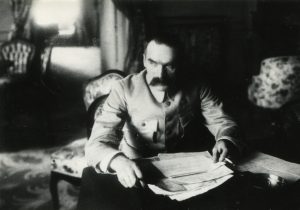

Piłsudski understood that Poland was too weak to stand up to the rebirth of Russian and German imperialism on its own. Hence he planned to create a federation of nation states encompassing Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic Republics in order to create a significant power lying between Germany and Russia. In Piłsudski’s opinion this was a means of permanently safeguarding the independence of Poland and the other countries in the region.

An attempt to implement Piłsudski’s plan was made by signing a pact with Symon Petlyura’s Ukrainian People’s Republic in April 1920 then undertaking joint military action with the Ukrainians to try and gain independence for Ukraine: however this ended in failure. The attempt to persuade Lithuania to join a federation with Poland also ended without any success. The operation in which forces led by General Lucjan Żeligowski captured Vilnius — not an officially sanctioned operation, but one instigated by Piłsudski — was supposed to serve this purpose. The incorporation of the Vilnius region into Poland as a result of this operation was in accordance with the wishes of a clear majority of the inhabitants of the region, but it caused prolonged conflict with Lithuania.

The federal concept was linked to a Promethean plan whose implementation was made possible by the collapse of the Russian Empire. This plan involved the creation of a string of nation states in the east starting from Finland and the Baltic States and stretching through Ukraine as far as Transcaucasia. These countries would have formed a natural alliance with a Poland strengthened by federation with the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lithuania and Belarus) and so together they could have created an effective barrier to Russian expansionism. These propositions were met with reserve and negativity from many Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Belarusian politicians as well as clear hostility from Russia.

Piłsudski’s federal plans did not come to fruition. Neighbouring states and nations were not in a hurry to form closer links with Poland. The political map of Poland and central and eastern Europe was closer to reflecting Dmowski’s thinking. Twenty years later, in 1939–1940, Germany and the Soviet Union would parcel out the countries of central and eastern Europe between them and deprive them of their sovereignty.