‘As we carry out our social reforms we hear our opponents crying out, “But that’s Bolshevism!” This is not Bolshevism. It is not even socialism. It is democracy. My goal is simply to catapult Poland from the eighteenth century into the twentieth…’

Józef Piłsudski

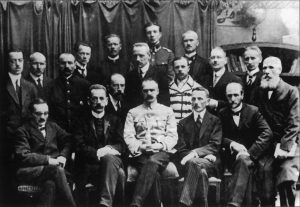

Józef Piłsudski actually implemented the majority of the policies in the Polish Socialist Party’s 1892 manifesto. As Head of State he brought in new democratic laws relating to universal rights for citizens including: equality for all regardless of gender, race, nationality or faith; local government; universal education for all; freedom of speech; freedom of the press; and freedom of assembly. He also introduced modern social reforms.

Despite the economic problems faced by the newly re-established Polish state one of the first legal instruments approved by Piłsudski was a package of edicts governing workers’ rights. An edict in respect of an 8-hour working day and a 46-hour working week was issued as early as November 1918. In December a ban on working at night, on Sundays or Holy Days was brought in, plans to limit durations of work harmful to health were announced, a ban on evicting unemployed people from modest accommodation was introduced and the right to strike was granted. In January 1919 edicts were issued on the subject of workplace inspections, employee sickness insurance and job placement services intended to assist jobseekers — these had an important function in view of the growing levels of unemployment. In the following months trades unions were given legal rights and the legal framework protecting workers’ interests continued to be expanded.

These actions put Poland ahead of some of the most developed western nations in terms of social welfare. In May 1919 Piłsudski countered the arguments of those opposing these developments thus,

‘As we carry out our social reforms we hear our opponents crying out, “But that’s Bolshevism!” This is not Bolshevism. It is not even socialism. It is democracy. My goal is simply to catapult Poland from the eighteenth century into the twentieth…’

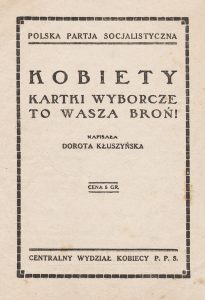

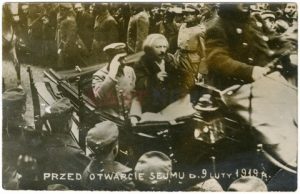

Another important decision made by Józef Piłsudski while Interim Head of State was to oblige the government to convene a parliament. On 28 November 1918 a decree was issued laying down electoral rules based on a democratic right to vote and the principles of universal suffrage, secret ballots, equal voting rights, direct voting and proportional representation. Women were given the right to vote which at the time was not yet common in Europe, let alone worldwide. All political groupings that wished to do so (including the communists) were allowed to stand in the elections. The government facilitated a fully democratic election campaign, freedom of association, freedom of the press, freedom to hold rallies and demonstrations. In January 1919 Piłsudski said,

‘As a person brought up striving for freedom I am against any limitation of the freedom of speech as born out by my opposition to the proposed legislation to protect my person from attacks by the press.’

Józef Piłsudski was a politician who was very sensitive to issues to do with freedom, workers’ rights and social welfare rights. He was a democrat. His actions showed that he wished to build a democratic state for the benefit of all Poles. He took care to make necessary compromises with all the different political groups. Piłsudski was profoundly convinced that the establishment of an independent state would calm the main political and social tensions and encourage the whole of society to work for Poland’s benefit.