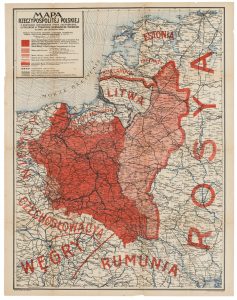

When Poland was reborn after 123 years of subjugation it did not have defined borders. Returning to the position in 1772 was not possible both because of the need for good relations with neighbouring countries and also because of the nation-building processes which had spread through central and eastern Europe during the nineteenth century. The road to delineating Poland’s borders was long, difficult and bloody and involved diplomatic endeavours, armed rebellions and plebiscites along the way.

The first areas to gain freedom were the lands in the Austrian Partition and the territories in the Russian Partition which had been occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Alongside them was Cieszyn Silesia which had not in fact been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, although the majority of its inhabitants were Poles. The liberation of these areas started in the second half of October 1918.

On 1 November battles with the Ukrainians for western Galicia broke out. The war with the West Ukrainian People’s Republic lasted until the summer of 1919 and ended with Poland gaining victory. The Ukrainian forces were driven back past the line of the river Zbruch which was the proposed dividing line for the Polish-Ukrainian border (and also the old border between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia).

In the first half of November 1918 the territory occupied by the Germans that was once Congress Poland was liberated; it included the country’s capital Warsaw. Thanks to the agreement between Józef Piłsudski and the German Military Council this was done without shedding blood. However the Germans did remain in the eastern territories of the previous Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in accordance with the terms of the Armistice of Compiègne and their evacuation to the Reich was a relatively slow, phased process. Departing Germans were replaced by Bolsheviks who established their own political and social order.

Establishing the border with Germany was a difficult problem. The Germans had been defeated in the west and so tried to minimise their territorial losses in the east and keep as many of the Prussian territorial conquests of preceding centuries as they could. In December 1918 a Polish insurrection broke out in Poznań, then spread to the whole of Wielkopolska and led to the liberation of this part of Poland.

Both Józef Piłsudski and the politicians making up the Polish National Committee in Paris were counting on the support of the western powers. At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference a decision was taken to incorporate Wielkopolska and Eastern Pomerania into Poland with a narrow stretch of land giving access to the Baltic Sea. Plebiscites were to be held among the inhabitants of Upper Silesia and in Warmia and Masuria on the question of whether these lands should belong to Poland or Germany. Gdańsk was to become a Free City.

In the period leading up to the Upper Silesian plebiscite relations between the Poles and the Germans became very  tense which resulted in two insurrections (in 1919 and 1920) of the Polish inhabitants of the area in response to German harassment. The Upper Silesian plebiscite did not go the Poles’ way. Following a third uprising in 1921 the disputed territory was divided in a way more beneficial to Poland. The plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria took place at the same time that the Polish Army suffered defeat at the hands of the Bolsheviks and so the result was a disaster for the Poles. Only a few scraps of disputed territory were incorporated into Poland.

tense which resulted in two insurrections (in 1919 and 1920) of the Polish inhabitants of the area in response to German harassment. The Upper Silesian plebiscite did not go the Poles’ way. Following a third uprising in 1921 the disputed territory was divided in a way more beneficial to Poland. The plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria took place at the same time that the Polish Army suffered defeat at the hands of the Bolsheviks and so the result was a disaster for the Poles. Only a few scraps of disputed territory were incorporated into Poland.

The border with Bolshevik Russia was demarcated as a result of the 1919–1920 war. Poland defended its independence and pushed the Bolshevik danger quite far to the east though not far enough to regain its pre-Partition border. The line of the border with Russia was set in the Treaty of Riga which was signed in 1921.

A territorial dispute arose with Lithuania over the Vilnius region where the majority of the population was Polish. However in the eyes of the Lithuanians Vilnius was their historical capital and the Vilnius region an integral part of their country. Acting on orders from Józef Piłsudski General Lucjan Żeligowski took control of the disputed territory in October 1920 in a military operation staged to look like a mutiny; from Vilnius he proclaimed the area to be the Republic of Central Lithuania, which in 1922 was incorporated into Poland. This caused long-lasting and bitter conflict with Lithuania. For many years the Lithuanian governments treated the border with the Polish state as no more than the dividing line in a truce.

The border conflict with Czechoslovakia related primarily to Cieszyn Silesia which historically was one of the lands of the Czech Crown (although earlier it had been a duchy belonging to the Piast dynasty, a line of Polish princes) however the majority of its inhabitants were Polish. In January 1919 the Czechs seized a large part of the disputed territory by force. The planned plebiscite addressing the issue of the national affiliation of these lands did not take place. In 1920 in accordance with a decision taken by the western powers the Cieszyn Silesian territories lying to the west of the river Olza were incorporated into Czechoslovakia without taking into account any ethnic criteria.

Demarcating the territorial shape of the re-established Polish state took several years and required significant human and material resources. A high price had to be paid for this in terms of conflict with neighbouring states which made normal relations with other states and peoples difficult. Latvia and Romania were the only neighbouring countries with which the Polish Republic had no significant border issues.