In the eighteenth century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth plunged into a crisis of the economy and of the political system. Ravaged by wars and badly governed, the country was not in a fit state to defend itself from the aggression of its powerful neighbours: Russia, Prussia and Austria. It is true the Poles embarked on a mission of fundamental reform — on 3 May 1791 the parliament passed the first European constitution, which gave grounds for hope the country would grow stronger — but despite that, as a result of three successive partitions in 1772, 1793 and 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth collapsed. Endeavours to regain independence during the nineteenth century did not manage to achieve their goal. Even the largest national uprisings in 1830–1831 and 1863–1864 ended in failure and intensification of the oppression of native Poles. As a consequence of this some Poles accepted that it was necessary to change the shape of the battle for independence: they believed the ruinous armed struggles should be replaced with “organic work”.

At the turn of the twentieth century the campaign for independence was resumed by a movement directed by Józef Piłsudski the leader of the Polish Socialist Party. Piłsudski intended to undertake an armed struggle with Russia which controlled the largest part of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and was the most brutal of the partitioning powers in oppressing Poles on ethnic grounds. Piłsudski was aware that to have any chance of success in an armed struggle against tsarism he would need to find an ally in one of the other partitioner states. He chose Austro-Hungary where Poles had more freedom to express their national identity than in the other Partitions. To a large extent it was due to his initiative that Polish paramilitary formations were set up in the Austrian Partition. In August 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War, these formations supplied the core of the Polish Legions which fought against Russia on the Eastern Front. The most famous of the Polish Legions was the First Brigade commanded by Józef Piłsudski.

After the Germans and Austro-Hungarians occupied the Kingdom of Poland, on 5 November 1916, the rulers of these

countries issued a proclamation: it announced the creation of a vassal, allied state called the Kingdom of Poland with a body called the Provisional Council of State in place of a government and with an army. This state was to include ‘lands recaptured from under Russian control’ and have links, which were not clearly defined, to the Central Powers. After the February Revolution of 1917 the Provisional Government in Russia acknowledged the Poles right to self-determination; shortly afterwards the United States of America declared war on the Germans. Piłsudski decided that Poland’s best interest was not served by continuing to co-operate with the partitioning powers ie Germany and the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. That was the reason why on Piłsudski’s orders the majority of the legionnaires refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Central Powers. In response the Germans interned Józef Piłsudski. After the oath of allegiance crisis in 1917 the whole of the Provisional Council of State resigned. It was replaced by the Regency Council.

The weakness of Germany and Austro-Hungary in the last months of the First World War facilitated a gradual assumption of power by the Poles. Independent Polish governmental bodies began to establish themselves. As early as 19 October 1918 the National Council of the Duchy of Cieszyn was constituted. On 28 October in Kraków the Polish Liquidation Committee was set up and it began to govern the western part of what was previously the Austrian Partition. The Provisional People’s Government of the Republic of Poland was set up in Lublin during the course of the night of 6–7 November 1918 and on 11 November the Supreme People’s Council was created in Poznań.

During the final stages of the First World War the Polish Military Organisation, which had been created back in 1914 by Józef Piłsudski, worked very intensively in Polish territory towards the goal of independence. In October and November 1918 the Polish Military Organisation began to disarm whole units of the occupying forces in both Galicia and the Kingdom of Poland.

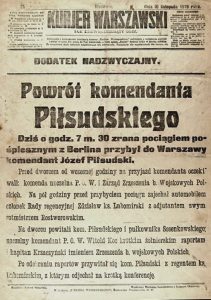

Kurier Warszawski, dodatek nadzwyczajny z 10.11.1918 roku

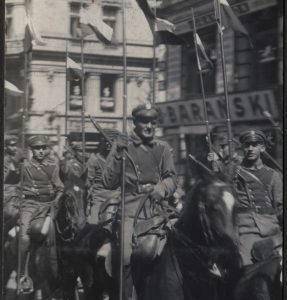

Józef Piłsudski arrived in Warsaw on 10 November 1918 after being released from Magdeburg Fortress by the Germans. On 11 November, on the day when the armistice agreement between the Entente Powers and Germany was signed in Compiègne ending the First World War, in Warsaw the disarmament of the Germans began and the Regency Council handed over supreme command of the army to Piłsudski. Three days later it ceded all political power to him and dissolved itself. On 16 November 1918 Piłsudski signed a dispatch notifying the governments ‘of all belligerent and neutral countries’ that a new independent Polish state was now in existence. This idiosyncratic “declaration of independence” was broadcast at some point on the night of 18–19 November from the radio station in the Warsaw Citadel which had been captured specifically for this purpose as it had hitherto been in German hands.

This statement contained assertions that were fundamental to Józef Piłsudski’s political thinking. The declaration affirmed that ‘an independent Polish state, taking in all the territories of a united Poland’ had now appeared on the map of Europe. This statement was an expression of the aspiration to unite all the different Polish territories that were under foreign control. The declaration also emphasised that thanks to the victories of the western powers

‘the reinstatement of Poland’s independence and sovereignty was henceforth a fait accompli.’

However the deciding role in regaining freedom was accorded to the Poles themselves. The dispatch emphasised that ‘the Polish state is being established in accordance with the will of the whole nation’ and then ‘it is based upon democratic principles and the Polish government will replace the rule of force…by a system built on the basis of order and justice.’ In the dispatch Józef Piłsudski very emphatically highlighted Poland’s resolve to defend its independence stating that, ‘…henceforth no foreign army shall enter Poland until we have formally communicated our will in the matter.’ To conclude he emphasised once more that Poland belonged among the democratic western nations.

This declaration of independence contained a succinct statement of the principles that were to guide the reconstituted Polish state. In it Józef Piłsudski outlined both the framework and the agenda for action. The following months were to bring methodical implementation of these announcements.