At the beginning of the twentieth century the Polish cause did not feature in European politics. No-one had any intention of raising it during the initial stages of the First World War. Both sides in the conflict did attempt to enlist the support of the Poles by luring them with promises, but they did not offer any formal guarantees in exchange for support. After the occupation of the Kingdom of Poland’s territory in the summer of 1915 the Central Powers divided up the spoils with each establishing its own occupation zone.

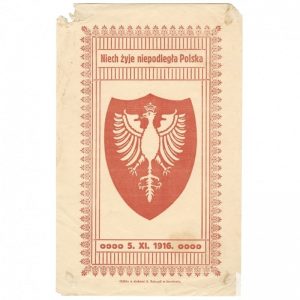

Midway through 1916 the Central Powers, Germany in particular, started to experience a shortage of recruits. In order to bolster their forces and take advantage of Polish soldiers whose military value had become evident (eg during the battle of Kostiuchnówka) the Germans decided to issue a proclamation supporting the existence of the Kingdom of Poland and then call up a Polish army under German command. That was the reason why the Act of 5 November 1916 came into being. This document announced the reconstruction of the Polish state. However this new Kingdom of Poland, whose borders were not specified, was not intended to be a sovereign state, but a dependency of Germany and Austro-Hungary.

The Act of 5 November 1916 was a breakthrough which made the Polish question prominent on the international stage because it put into motion a chain of events. It started the bidding war for Polish support that Józef Piłsudski and the Polish independence movement had long desired. In response Tsar Nicholas II issued a New Year’s Day order to the army and fleet which announced that Poland would be reconstructed as a free and united country, although it would continue to be bound to Russia.

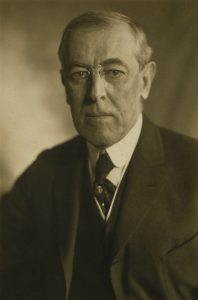

Far more significant was the address of the President of the USA Thomas Woodrow Wilson to the Senate on 22 January 1917 in which he said,

‘…statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, and autonomous Poland.’

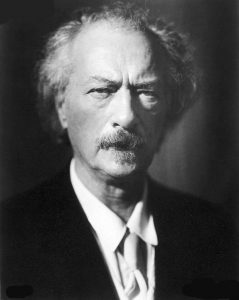

President Wilson’s standpoint was influenced to a degree by the distinguished Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski who was sometimes referred to as “the best advocate for Polish independence”: at the President’s request Paderewski had prepared a memorandum on the Polish issue for him.

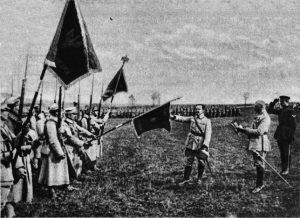

The outbreak of the February Revolution in Russia and in particular the documents produced by the new government which acknowledged Poland’s right to independence brought the Polish issue to life in England and France as henceforth it was no longer considered to be an internal Russian problem. The governments of the western nations were now ready to support the Polish cause in order to outbid Germany. They were particularly worried by the possibility of the Germans constructing a Polish army. As a result the Polish Army in France was created on 4 June 1917 and the Polish National Committee (at first based in Lausanne and later in Paris) was officially recognised as representing Poland’s interests. The existence of this Polish Army was one of the factors leading to Poland being treated as one of the Allied states by the Entente Powers.

Meanwhile on 12 September 1917 the Central Powers established a Regency Council (until such date as a King was chosen) in order to regain the initiative with regard to the Polish question. Under the control of the occupying forces the government reporting to the Regency Council started to construct the elements of a state apparatus for Poland. Right up to the very end of the war the Central Powers tried to maintain their political and economic influence in Poland. After the Bolshevik revolution the new government in Russia gave numerous assurances of Poland’s right to independence, yet in reality they treated the issue as a matter of expedience and their real aim was to subjugate Poland by turning it into a Soviet republic.

Woodrow Wilson in London, 1919

Meanwhile in the west President Wilson announced a programme for rebuilding the world following the war. In a fourteen-point presidential address given on 8 January 1918 the 13th point supported the creation of an independent Polish state, ‘…which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea.’ The next step on the road to Poland regaining independence was a declaration on 3 June 1918 by the Prime Ministers of France, Great Britain and Italy which stated that,

‘…the foundation of a united and independent Poland with access to the sea is one of the conditions for…peace…in Europe.’

The imminent defeat of Germany and Austro-Hungary led to a staged process of liberation occurring on Polish territory. At the start of October 1918 the Regency Council made a formal address to the Polish nation advocating an independent state. In the second half of the month Polish governmental bodies independent of the partitioning power authorities were constituted in Cieszyn and Kraków and at the beginning of November also in Lublin. The process of creating the foundations of a free Poland had begun.

On 10 November 1918 Józef Piłsudski arrived in a Warsaw still occupied by the Germans. His first move was to come to an agreement with the rebellious German soldiers and as a consequence of this he managed to take power in the city without bloodshed. The other political groupings with power in Poland accepted he was in command. Within a few days in a dispatch that announced the creation of a Polish state he was able to write,

‘Poland’s political situation and the yoke of occupation have hitherto prevented the Polish nation from freely expressing itself about its own fate. Thanks to the changes which have occurred as a result of the glorious victories of the Allied armies the reinstatement of Poland’s independence and sovereignty is henceforth a fait accompli.’

As a consequence of the First World War Russia, Austria and Germany suffered decline. Due to the breakdown of the multinational empires of Austro-Hungary and Russia many other nations in central and eastern Europe besides Poland regained or gained independence: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later to become Yugoslavia) and Hungary. The Ukrainians and Belarusians also fought for independence.

These events were in line with the objectives of the President of the United States Thomas W Wilson whose political ideology aimed at the development of better, fairer international relations throughout the world.